Research

Understanding the evolution of microbes is important; we need to prevent them from developing antibiotic resistance and other dangerous mutations. My PhD focused on experimentally, analytically, and numerically describing the evolutionary dynamics of growing microbial colonies on solids and viscous liquids. Growing microbial colonies on solid surfaces are often called “biofilms.” As evolution is random, I extensively utilized probabilistic techniques to analytically model and numerically simulate my experiments. I also created hundreds of IPython notebooks to analyze my experimental data. The GitHub repositories and IPython Notebooks that I developed during my PhD can be seen on the Computation page.

Evolution on a Solid Surface

Experimental Setup

The standard experiment I conduct in the laboratory is quite simple. I take multiple identical strains of E. coli differing only by the fluorescent protein they produce (their color), mix the strains together in liquid growth media, and deposit a droplet of the media roughly 2mm in diameter onto the surface of a nutritious agar plate. Once on the agar surface, the E. coli use the local nutrients to grow and proliferate (E. coli reproduce by creating clones of themselves, or budding; they do not have sex). The growth of a population into virgin territory is called a range expansion.

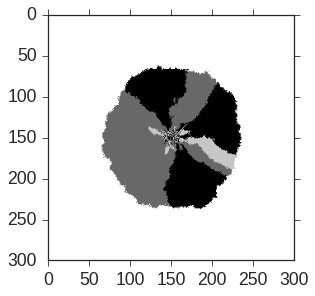

The wiggling (i.e. diffusion) of the E. coli on the agar plate coupled with their growth results in the colony expanding. The movie below show the growth of three strains of E. coli on an agar plate after initial inoculation. Naively, one would expect that as the colony grows, the different strains of E. coli would remain mixed resulting in a blend of all the colors. Surprisingly, past a certain radius, the colony segregates into one local color, forming beautiful patterns. My PhD focused on understanding these patterns and the resulting microbial colony evolutionary dynamics. I created many GitHub repositories and IPython Notebooks to quantify the results of these experiments (see the Data Analysis page).

Similar patterns can be seen in different geometries. In the below movie, I again inoculated three different colored strains of E. coli in equal proportions on a strip of filter paper. I placed the filter paper on an agar plate and imaged the colony growing.

Stochastic Models of Colony Growth

Why do these patterns form? The E. coli in our experiments are not doing anything strange: they simply grow and divide at roughly the same rate. Ultimately, it can be shown that the patterns are created because the small population size of the thin growing layer at the front of the colony magnifies stochastic number fluctuations.

A layer of about 5 to 10 cells are actively growing at the front of the colony at any time. If, by chance, several red cells divide before others nearby, there is a good chance that the red cells will take over if the local population size is small. A standard mathematical model to describe two competing strains (i.e. the red and blue color) in a colony is the “Stochastic Fisher-Kolmogorov-Petrovsky-Piscounov” (FKPP) equation and can be expressed as

is the population density of one of the two strains and is a function of space and time . The population, due to the wiggling of E. coli, diffuses with a diffusion constant and grows at a rate specified by . Due to overcrowding, the population saturates at a density of . The final term is the most interesting and describes how stochasticity impacts the evolution of the colony. describes how many cells locally compete at the front of a colony, and is Gaussian white noise with mean zero and variance 1 and is distributed over space with the property that

As decreases, i.e. the growing colony layer becomes more thin, the stochastic term on the far right becomes larger and larger. If the stochastic term on the far right is large, fluctuations in the local population density of a certain strain color will be large, and the absorbing points or will be randomly reached, resulting in the total dominance or extinction of a color locally.

An image from a numerical simulation of the SKFPP equation that I created is shown below. Throughout my PhD, I used this equation and various analogs to simulate my experiments; my simulation GitHub repositories can seen in the Scientific Computing page. The SKFPP equation is trickier to work with than typical stochastic differential equations because of the spatial diffusion term (); the local growth and competition between the strains is coupled with their diffusive transport.

Paper: Many Colored Strains with Differing Growth Velocities in a Range Expansion

In a paper I wrote, I studied the evolutionary dynamics of many competing strains (colors) of E. Coli with differing expansion velocities. I applied both experimental and numerical techniques to investigate this problem and created a rigorous procedure to fit my numerical models (analogous to the SKFPP equation above) to experimental data. I showed that by utilizing a data collapse I observed numerically, I could fit new experimental parameters to unprecedented levels of accuracy and predict the dynamics of an arbitrary number of competing strains.

Evolution on a Viscous Liquid’s Surface

Experimental Setup

Many organisms do not live on solid surfaces; they instead live in liquid environments, such as fish or phytoplankton in the ocean. In the ocean, a new form of transport is introduced: advection, or the transport of material by fluid flow. How does advection couple with the diffusive-induced growth discussed above to alter the evolutionary dynamics of populations? We are interested in a regime where the flow is not strong enough to totally mix a colony.

To the best of my knowledge, nobody has created an easy-to-use, well-controlled laboratory system to study this question. I teamed up with my colleague Severine Atis to solve this problem. We are writing a paper on our work now. I have created a variety of fluid mechanics simulations to explore this topic in the Scientific Computing page.

Stochastic Models of Colony Growth with Advection

We can now take the same equation from before, the SKFPP equation, and add a velocity field that advects microbes:

This seemingly small change can dramatically alter the evolutionary dynamics of growing colonies; I explore this in the paper I am writing with Severine.