Computation: Scientific Computing

My scientific computing projects have focused on both fluid mechanics, relevant to the second half of my thesis, and simulating the stochastic evolution of microbial colonies.

1. Fluid Mechanics

An Award-Winning GPU-powered Lattice Boltzmann Simulation

As I knew the second half of my PhD would focus on fluid mechanics (as I was growing microbes on an ultra-viscous liquid), I audited Sauro Succi’s computational fluid mechanics course in hopes that I could create experimentally relevant simulations. Sauro played a pivotal role in the development of the Lattice Boltzmann technique, a relatively new mesocopic technique that excels when simulating multiphase fluid flow and flows in complex geometries (such as porous media).

Based on the material I had learned while auditing Sauro’s class, I created my own GPU-powered 2-dimensional Lattice Boltzmann simulator in collaboration with @matheuscfernandes as the final project for CS205 (one of my required courses to obtain my minor in Computational Science and Engineering). Relative to naive Python, our GPU-powered simulation obtained a speedup of 650x, and, relative to single-threaded cython, a speedup of about 50x. Additional information about the Lattice Boltzmann technique, our simulation, and our procedure to optimize the speed of our package can be seen on the 2d-LB website. The video below illustrates a simulation of fluid flow around an obstacle at moderate Reynolds number, and the rather humorous video below that discusses our simulation in greater detail. The IPython notebook used to create the video is linked here.

After completing the final project for CS205, I wrote a proposal to the Institute for Applied Computational Sciences at Harvard asking them to fund work extending the simulation; I wanted to add real-time visualization of fluid flows with vispy (OpenGL) and add the transport of passive scalars by fluid flow (a situation relevant to my experiments). IACS awarded me a $25,000 student scholarship and I completed those additions. This was one of my favorite projects during my PhD.

Buoyant Flow in the Stokes Regime

The Lattice Boltzmann Technique is an excellent explict time-stepping technique; it works extremely well when dealing with problems of Reynolds number 0.01 to approximately 50,000. However, for smaller Reynolds numbers where the time-evolution of a flow can largely be ignored, i.e. the Stokes regime, more efficient techniques exist as they can quickly seek out the steady state flow in a non-physical manner (i.e. the numerical scheme can violate physical laws when approaching the steady state as long as the final state does not violate any laws; the Lattice Boltzmann technique obeys physical laws at every time step and is consequently more slow in this case).

The experiments I worked with in the lab had Reynolds numbers as small as 1e-9 due to the extreme viscosity of the fluid I was working with and comparatively small experimental setup (on the order of 10cm). I consequently learned how to use OpenFOAM, a standard open-source fluid mechanics solver, and created my own OpenFOAM-based Stokes-Flow solver to model buoyant flows that our cells produced (the paper on this topic is in preparation). The below video illustrates the time-evolution of a radially-symmetric buoyant flow induced by cells (orange line) growing on the bottom of a closed container. The intensity of the colormap is the magnitude of the nutrients surrounding the cells; as time progresses, the cells eat more nutrients and the color becomes darker. A characteristic “plume” opposing the direction of gravity is witnessed.

2. Random Walks and their Application to Microbial Evolutionary Dynamics

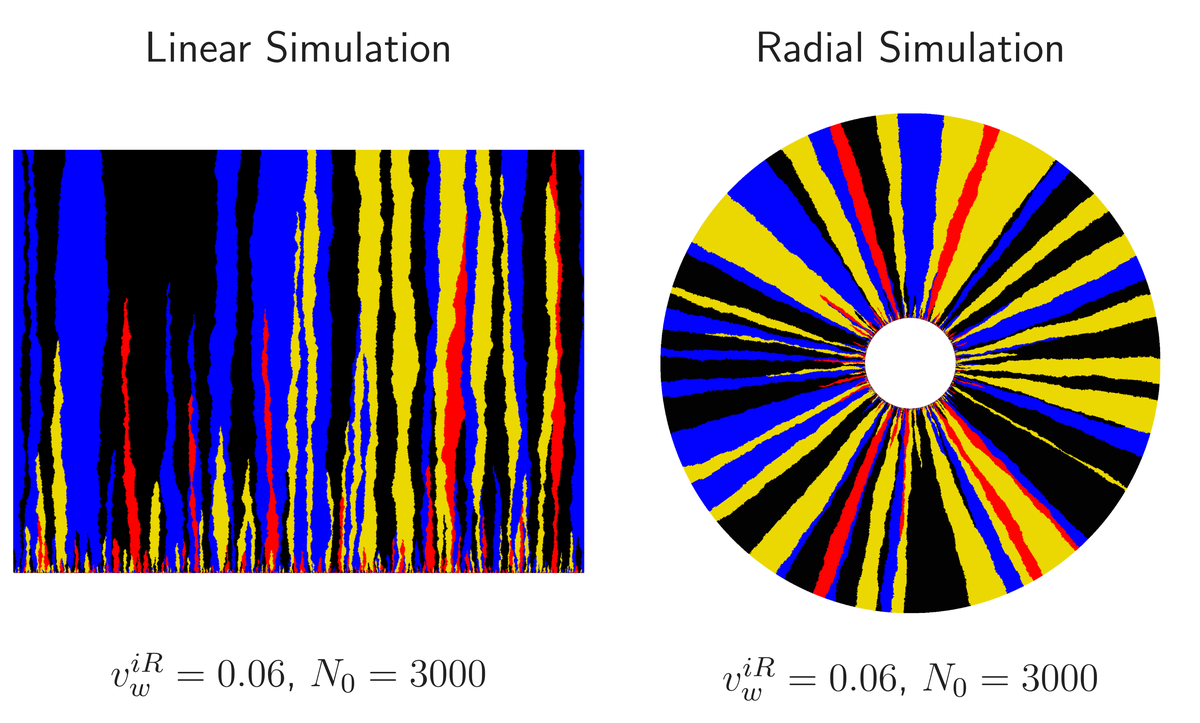

The first half of my thesis focused on understanding how to use probabilistic techniques involving random walks, markov processes, etc. to gain insight into the stochastic evolutionary dynamics of microbes (evolution is quite random!). I was particularly interested in modeling the evolution of multiple growing strains in microbial colonies (represented by different colors in the images below). I authored most of the code in the “Range Expansion” Github organization and will summarize some of my projects on the topic below.

Annihilating and Coalescing Random Walkers

The object-oriented cython and cython-gsl-based simulation package developed for a paper I wrote. It simulates random walkers constrained to lie on the edge of an inflating 1-dimensional ring that either annihilate or coalesce when they collide, mimicking the domain walls separating different strains of microbes in my colonies. In reality, the edge of a microbial colony is rough and randomly undulates; in this simulation, we treat the colony as perfectly smooth for simplicity. Using this simulation, I discovered an interesting data collapse that allowed me to precisely quantify extremely small growth rate differences between competing microbes (after coupling my simulation to experiment), and also predict the dynamics of an arbitrary number of competing strains with differing growth rates. The below image was created using this repository and illustrates that the model produces figures qualitatively similar to my experiments.

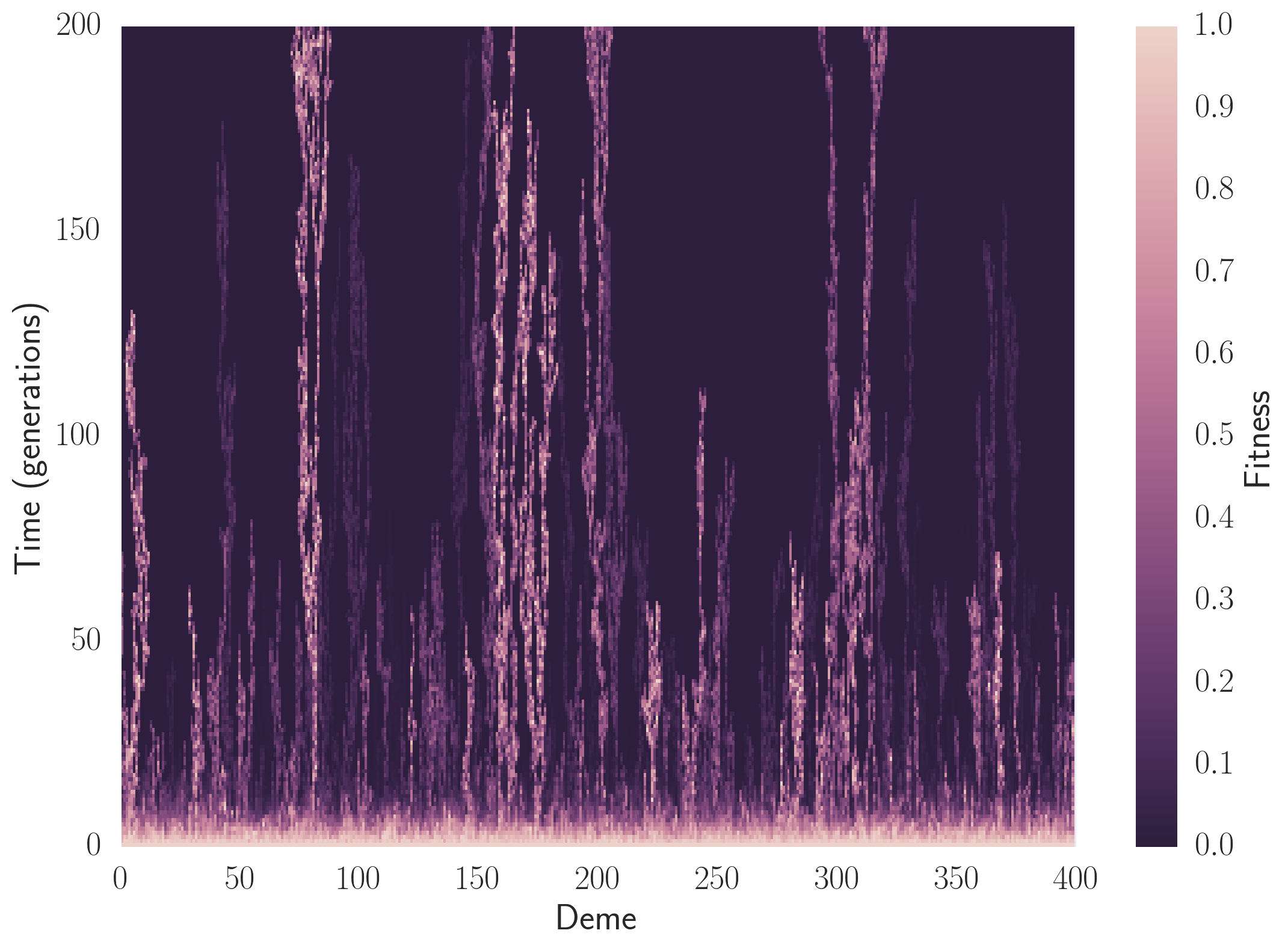

The Stepping Stone Model

We again couple cython and cython_gsl to study an analog of the above simulation. We treat microbial colony as a ring of connected islands. Microbes migrate between the islands and stochastically evolve. The “Annihilating and Coalescing Random Walker” simulation is a special case of this one where the local island population approaches 1. The striking image below illustrates a phenomenon called “Mueller’s Ratchet”, where if microbes have a large enough mutation rate and enough of the mutations are deleterious, the population’s fitness (how bright the image is) will utterly collapse. Sex helps to prevent this catastrophe. The linked IPython Notebook illustrates how to use this package.

Bulgey Colonies

We now relax the perfectly smooth assumption; faster growing strains now create a smooth bulge in the colony. How does this change the growth dynamics? I created a repository to simulate this scenario utilizing the the fast marching method (scikit-fmm). In the below movie, the blue strain expands faster than the green strain which expands faster than the red one. Beautiful shapes (that we see in experiment!) are created.

Bulgey Rough Colonies

If we allow bulges to be created due to strains’ differing expansion velocities but now relax the assumption that the bulges are smooth, we must account for stochastic undulations that build up at the front. We use a lattice-based algorithm, the Eden Model, to explore this problem. A short IPython notebook can be seen illustrating how to use the package.